The Case for Using a Certified Deaf Interpreter

The Case for Using a Certified Deaf Interpreter

The Case for Using a Certified Deaf Interpreter

For many in the Deaf and hard of hearing community, working with interpreters is a significant part of their reality—in medical, legal, professional, educational and even entertainment settings. So imagine the relief they feel when their interpreter communicates with the same signs, expressions and understandings that they use with their Deaf friends and family. And imagine all that could go wrong if a less qualified interpreter was relied upon for say, a critical medical or legal situation.

Generally, the interpreters who are understood most clearly by Deaf people are interpreters who themselves are Deaf. Those who meet the rigorous standards of the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (RID) become Certified Deaf Interpreters, or CDIs, and in the world of American Sign Language (ASL) interpreters, they possess a particularly valuable skillset. (Indeed, the same can be said for many working deaf interpreters who are on the path to becoming certified.)

None of this is meant to diminish certified hearing interpreters, many of whom are deeply immersed in Deaf culture and perform admirably. More likely than not, though, they will be among the first to recognize when a particular situation is best served by a CDI—and proactively recommend engaging one.

The Value of the CDI

What the CDI brings, in addition to excellent general communication skills and training as an interpreter, is extensive knowledge and understanding of deafness, the Deaf community and Deaf culture. A CDI is a language specialist who is able to navigate and mediate the inherent differences between the hearing and Deaf communities, while enhancing the accuracy, meaning, and effectiveness of the interpretation. In turn, the Deaf consumer recognizes that they’re not the only Deaf person in the room—that the CDI lives a similar life and can appreciate their perspective. These factors help establish trust and give the CDI a solid connection to the Deaf consumer.

Recommending a CDI isn’t always easy, however, because in most cases, the CDI needs to work in tandem with a hearing interpreter, adding to the cost. Still, the benefits CDIs deliver aren’t easily dismissed. With CDIs, all parties are more likely to reach optimal understanding, including clarification of any linguistic or cultural content. Time and resources are applied efficiently. A clear conclusion and agreement is more likely to be achieved.

Costs savings can be a factor as well, particularly in medical and legal situations, by limiting the potential for added costs down the road if poor communications adversely affect decision-making.

How CDI’s Work

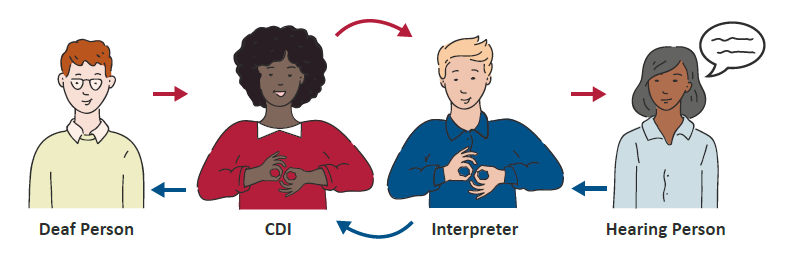

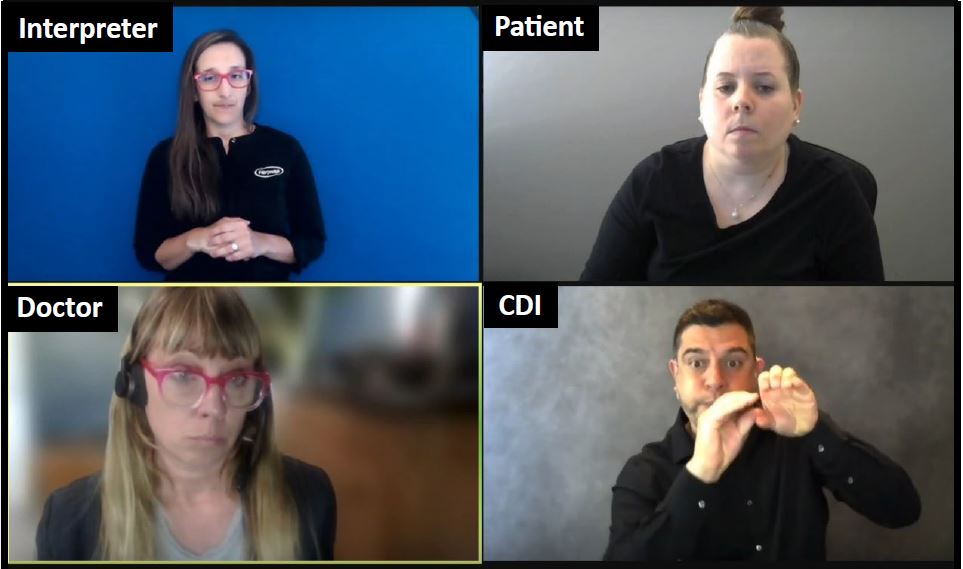

When they work together, the CDI and the hearing interpreter provide a two-person communications chain between a Deaf person and a hearing person. At a doctor’s appointment, for example, the Deaf patient signs to the CDI, who then signs to the hearing interpreter, who speaks to the doctor. The chain is reversed when the doctor speaks. It looks like a message relay, but it’s more than that. Each interpreter processes the message linguistically and culturally, then passes it along in the ways that are most appropriate to the respective consumers.

The two interpreters also support one another, serving as a second set of eyes or ears to monitor accuracy and, in particularly challenging cases, conferring to arrive at the best possible interpretation. By taking turns, they also reduce mental fatigue, which can lead to errors. Indeed, some states require at least two interpreters team up to work certain legal proceedings for these very reasons.

When to Engage a CDI

CDIs bring optimal interpreting skills to any situation, but they are especially valuable when:

- The proceedings may have a profound impact on the Deaf person’s life, such as in medical appointments and legal hearings.

- The Deaf person uses something other than standard ASL to communicate, such as a foreign sign language or nonstandard signs that are unique to a family (“home signs”), region, ethnic group or age group.

- The Deaf person also has other challenges, such as vision impairment, or limited educational background or communications skills.

- A broadcast or presentation seeks to reach a wide audience of Deaf people with different backgrounds and signing customs.

- The situation becomes emotionally charged, as can happen, for example, in encounters with law enforcement.

Challenges remain. We don’t have enough CDIs to meet demand today, and until this year, the RID had a multi-year moratorium on certifying Deaf interpreters while they revised the requirements. With the new certification process in place, we expect more Deaf people to be entering the field.

And while CDI acceptance has been growing steadily over the last two decades, we still encounter objections, so efforts to educate interpreter decision-makers must continue. To that end, the best arguments in the CDI’s favor are the examples of the CDIs themselves, who every day bring the highest level of ASL interpreting to tasks large and small throughout the nation.

About the Author

Michael recognized the need for an interpreter referral agency that valued consumers and interpreters alike and founded Interpretek in 1993. The company quickly earned a sound reputation nationwide for outstanding quality and high ethical standards. In 2019 Michael received NTID/RIT’s Distinguished Alumni Award for outstanding service to the community.

Contributing to the interpreting profession and supporting the Deaf community are important to Michael as demonstrated by Interpretek’s continuing education curriculum offered to interpreters and by establishing an Endowed Scholarship at NTID/RIT for students pursuing a degree in interpreting.

Michael and his wife Kate, also an interpreter, live in the Rochester area and have three adult sons. Michael is active in a variety of community organizations and best of all, enjoys spending time with his grandchildren.